Less than two months after his inauguration, Joko Widodo gave one of the most influential speeches of his presidency at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, his alma mater. The president said four crucial issues had to be immediately addressed: corruption, state ‘dignity’, fuel subsidies and narcotics.

Twenty days later the president would go on to abolish fuel subsidies and in May last year his government moved to ban domestic workers from traveling to foreign countries because Indonesia “should have pride and dignity.” Then it initiated a crackdown on illegal fishing to reaffirm the country’s sovereignty. Corruption and drug eradication, however, are ongoing issues with more complicated solutions, if any.

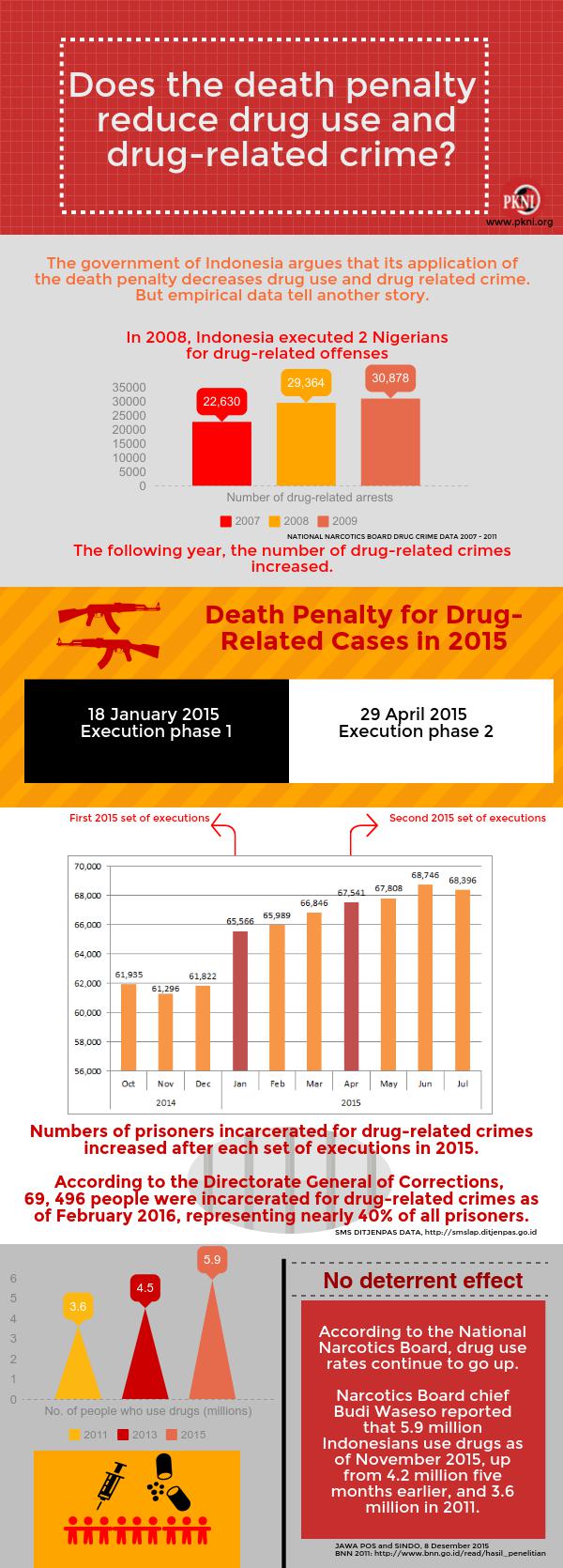

At the university, Widodo told a room full of students that he would reject 64 clemency requests from drug convicts on death row to send a strong message. The country, he claimed, was facing a “drug emergency: with around 4.5 million Indonesians using drugs, including 1.2 million who could not be cured of their addiction. Around 40 to 50 people, he claimed, were dying every day because of drugs. “Can you imagine it?”

But drug policy experts have difficulty imagining such a landscape, as Widodo’s figures are based on studies by the National Narcotics Agency (BNN) which have been discredited. Neither the Health Ministry nor any health agency around the country has ever suggested that some 300 people could be dropping dead each week because of drugs.

Indonesia’s drug problem is one of growing demand, social exclusion, untreated addictions and, above all, criminalization of the drug users who the government is supposedly trying to protect.

In the 17 months since the so-called ‘drug emergency’ was declared, the government has executed 14 drug convicts, scaled up drug raids and trialed mass rehabilitation programs, but nothing suggests this has led to any improvements. Ongoing major drug seizures, particularly of crystal methamphetamine, and a soaring prison population with some 43% of inmates jailed for drug crimes, tell a story of policy failures.

Concord Strategic asks whether the current ‘drug emergency’ is overblown and could be creating a social time bomb.

Acting blindly?

Public health and drug policy experts frequently draw attention to Indonesia’s unreliable data used to justify the so-called ‘drug emergency’.

In an analysis for Australian news website The Conversation, Claudia Stoicescu, a graduate student at Oxford University, noted last year that the figures used to justify the ‘emergency’ came from a study which used “questionable methods and vague measures.” She claimed that government advisers cherry-picked the figures to ultimately justify an ineffective but politically convenient policy.

One of the figures stated by the government is that 4.5 million drug users need rehabilitation. This figure is a projection of the number of people believed to have used drugs in 2013, calculated by the University of Indonesia’s (UI) Center for Health Research in collaboration with BNN based on a 2008 study.

The study also used an “overly simplistic definition of ‘addiction’,” based solely on how often an individual uses drugs. People who took drugs less than 49 times in the last year before the survey are classified as regular users and those above as addicts. Participants who indicated that they had injected a drug, even if only once in the last year, are also categorized as addicts. From this projection there were supposedly 2.9 million drug addicts in 2013.

Stoicescu said the figure of 40 to 50 young people said to be dying each day because of drug use is even more problematic. To determine the rate of drug deaths in the general population, the UI researchers surveyed 2,143 people and asked how many of their friends used drugs, and among these, how many of their friends died “because of drugs.”

Applying the median number of friends who died – three – to their 2008 estimate of drug addicts, the government arrived at a figure of 14,894. Divided by 365 days, this amounts to 41 “people dying because of drug use every day.”

Edo Nasution, who as the national coordinator of the Indonesian Drug Users Network (PKNI) has collaborated with Stoicescu, told Concord Strategic that BNN revised the number of deaths down to 30 to 40 from 40 to 50 after Stoicescu debunked their figures. “They don’t want to admit that they were wrong. (There was) no explanation for why they changed it. It happened two months after Claudia’s (article),” he said.

President Widodo publicly loosened the tally in April 2016 when he repeated his mantra to justify the death penalty for drug users during a meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel. “Thirty to fifty people a day die in Indonesia because of drugs,” he told her.

No accurate or recent statistics on drug use and drug-related deaths in Indonesia are available, which forces all health and crime-reduction organizations, including UN bodies, to rely on BNN’s numbers.

The only alternative tallies which Concord Strategic was able to find were two by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2008 and 2010. In 2008, the WHO put Indonesia’s death rate for drug use disorders at one per 100,000 population, nearly double that of the UK at the time; and in 2010, a WHO estimate showed that drug users per capita in Indonesia were among the lowest among major countries and three times lower than neighboring Australia.

The UN’s view

Concord Strategic asked the Indonesia country manager of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Collie Brown, whether he thought BNN or WHO estimates represented an accurate picture of Indonesia’s drug problem.

“That’s the thing. We don’t know. That’s one of the reasons we’ve been advocating to have a more recent, comprehensive drug use survey. Because I think they (WHO and BNN) use different numbers: WHO prevalence and then the (BNN) has numbers that the government cites,” Brown said.

Brown said UNODC has been working with BNN to offer a statistical method which captures in a much more comprehensive way the issue of drugs and their use in Indonesia. “What we (UNODC) typically look at with these surveys is age, but we also look at the attendant factors that result from drug use, such as injecting drug users for example.”

He said creating drug policy in Indonesia at present is challenging due to a lack of reliable figures.

An invisible emergency?

Concord Strategic asked Nasution whether he believes that increased drug crackdowns are creating a social or health ‘emergency’, harming the public more than it benefits from it.

“Yes, because it is after President Joko Widodo declared a war on drugs last year (that the situation got worse). At the ground level, the number of raids increased massively: forced urine tests…, people who inject drugs now become more hidden because they are afraid,” he responded.

Nasution said law enforcement officials began visiting methadone clinics run by the Health Ministry to ask for private medical records, which damaged the trust between providers of usage elimination or rehabilitation treatments and drug users.

Under the 2009 Narcotics Law, failing to report a drug addiction to the authorities is punishable with prison. Relatives of drug users can also be jailed for up to six months if they fail to report a known drug user in their family.

“In the first month (January 2015) of the war on drugs we had paralegal activities; we trained the community, people who use drugs, to become shadow lawyers to give legal assistance to people who get arrested for using drugs. We documented a lot of human rights violations, and bribes… basically law enforcement uses people who use drugs as an ATM machine: if you have money, they will release you, if you don’t have money they will send you to prison.”

“So, (the drug emergency) has had a lot of impact on (drug user) harm reduction and also the price of drugs. For example (the price of) heroin on the street has increased 600-700% and that’s huge. People who are addicted will not stop, so we are afraid petty crimes will increase due to their need to feed their addictions,” he said.

Nasution added that while BNN’s mandate is to reduce supply and demand of drugs, they keep targeting people who use drugs because they “are the easiest target.” PKNI has been documenting the social and health impacts of the war on drugs under Widodo’s administration and expects to release a report with its findings soon.

Defining rehabilitation

Brown and Nasution both agree that Indonesia needs public health approaches to drug use and demand if it wants to reduce the effects of drug use and addiction. “It is not only about law enforcement, it is also about treatment and rehabilitation. You can’t talk about one without the other and nobody has been able to arrest their way out of a drug problem,” Brown said.

Indonesia is unique in this regard. It has some of the world’s harshest laws against drugs but many government officials, including top law enforcers, repeatedly call for the rehabilitation of drug users. Nasution calls this a “double standard.”

Indonesia in 2009 reformed its Narcotics Law to introduce provisions allowing for the replacement of jail time for rehabilitation of drug users caught with small amounts of drugs. The changes set the foundations for a national drug policy that could prioritize drug use prevention through awareness campaigns and encourage drug users to play an active role in society after rehab.

In reality, however, a corrupt police and judiciary often means drug users are coerced to pay bribes to enter rehabilitation instead of jail or avoid both altogether. Drug users with limited resources often end up in jail serving longer sentences due to their inability to pay.

In addition, BNN’s position on whether drug users should be rehabilitated, not incarcerated, has flip-flopped since 2009. National Police Criminal Investigation Directorate (Bareskrim) chief Anang Iskandar, who served as BNN chief from 2012 to 2015, was in favor of rehabilitation instead of incarceration, even though his views were insufficient to reverse the trend.

When Iskandar swapped jobs with tough-talking former Bareskrim chief Com. Gen. Budi Waseso, BNN’s tone reverted back to the pre-2009 approach. After his appointment in September last year, Waseso said the 2009 law was being used by drug dealers to avoid heavier punishments by claiming to be drug addicts needing rehabilitation. He said rehabilitation was a waste of state funds which were being spent on “fixing broken people.” He hinted that anyone arrested for narcotics possession would be jailed.

Then, after several weeks, Waseso backtracked on his rejection of rehab and announced an ambitious plan to rehabilitate 100,000 drug users per year, a target apparently set by Widodo himself. This was branded as a last-ditch attempt by BNN to save drug users before moving to more strict policies.

The initiative was launched with a huge advertising campaign, including animated infographics at most electronic billboards throughout Jakarta. Drug users or their relatives were encouraged to report cases of drug use to BNN and join the rehab programs run by the Social Affairs or Health ministries. Rather predictably, BNN failed to meet the target of 100,000 rehab cases last year due to a “lack of infrastructure.”

According to Nasution, BNN briefly set a 200,000-target for this year before all targets were quietly scrapped in early 2016.

Even if the goals were achievable, BNN could still have failed to reach them. People who test positive for drugs are not simply sent to rehabilitation, they are often asked to pay bribes to avoid it. As for those caught with small amounts of drugs, they go directly into police or BNN detention where they have to bargain their way to rehabilitation or face ending up in jail.

Despite slogans about rehabilitation being available to all drug users on a voluntary basis, the reality is significantly different. “I asked them (BNN) ‘what do you mean by a voluntary-based approach? You still force people to take urine tests in schools and kos-kosan (boarding houses) to refer them to rehab – where is the voluntary aspect? It is still mandatory,” Nasution said.

Nasution said that while urine drug tests outside nightclubs have been common for around two decades, BNN only recently began raiding boarding houses and forcing students to undergo the tests.

Overcrowded prisons

The ongoing crackdown is contributing to enlarging Indonesia’s prison population at a time when prison riots in overcrowded jails have put the issue in the spotlight.

Around 43% of Indonesia’s prison population is serving time for drug convictions. A large yet undetermined portion of these convicts were jailed for use or possession of small amounts and, unsurprisingly, this has contributed to drug circulation being rife behind bars.

The UNODC country manager said Indonesia must introduce better drug treatment in prisons for those already jailed and conduct frequent raids to tackle the drug trade behind bars. “(The issue of drugs in prison) then brings other stuff with it, because if you have people being able to operate with impunity dealing drugs inside prisons, what else can they operate with impunity?” Brown said.

BNN claims that 60% of drug circulation in the country is being controlled by jailed drug pushers, a claim which the agency has used to justify a campaign of raids at penitentiaries, where prison guards and even wardens have been found to collaborate with prisoners to profit from the illicit trade.

This level of complicity appeared to be a factor in the April riot at the Banceuy Narcotics Penitentiary in Bandung, West Java, where 21 inmates and four police officers were injured in a fire inside the prison on April 23. Inmates reportedly became enraged at prison authorities trying to pass the death of 54-year-old inmate Undang Kosim as a suicide.

An inmate told the media that it was suspected that Kosim was tortured in an effort to get him to confess that he had tried to smuggle drugs into the prison. He was due to be released from prison in less than two months.

Nasution also believes there is resentment among prisoners jailed for drug possession for longer than five years, as they are not eligible to obtain sentence remissions like those jailed for shorter periods. In many cases, the length of sentences is decided by how much the suspect can afford to bribe police or court officials.

To tackle overcrowding, the Justice and Human Rights Ministry is currently reviving a plan to revise the 2012 government regulation which imposes strict requirements for remissions for prison inmates. The ministry’s Director General of Human Rights, Muallimin Abdi, said on April 27 that the revision is needed as the requirements do not view all inmates equally and violate the rights of inmates who have shown good behavior during their time behind bars.

Justice Minister Yasonna Laoly also submitted a request to recruit 11,000 prison guards this year to prevent violence at overcapacity penitentiaries, but the request does not appear to have made any inroads. As many as 183,282 prisoners are being held in 477 penitentiaries nationwide, exceeding their intended capacity by 145% and putting the prisoner-to-guard ratio at 50 to one during some shifts.

Lasting supply

Meanwhile, in the midst of a nationwide drug crackdown, major drug hauls continue to be intercepted, suggesting that demand for drugs is not declining despite the government’s efforts in recent years and, particularly, over the past 17 months.

Crystal methamphetamine, a highly addictive drug which ranks second in popularity in Indonesia after cannabis, continues to gain prominence. In line with trends in the region, arrests related to crystal methamphetamine have increased significantly in Indonesia since 2012, according to a 2015 UNODC report on the “The Challenge of Synthetic Drugs in East and South-East Asia and Oceania.”

The report says that in Indonesia and Malaysia, crystal methamphetamine seizures have fluctuated annually, the largest amount of seizures having been reported in Indonesia in 2012 at more than 2 tons and in Malaysia in 2013 at 1.7 tons. Similar or higher amounts were likely to have been intercepted in Indonesia in 2015, a year that began with a haul of over 800 kg of crystal methamphetamine seized in West Jakarta.

Most crystal methamphetamine found in Indonesia is believed to be manufactured in China but a rise in international drug networks controlling the substance has also seen methamphetamine produced in Africa entering the market. The UNODC report also questions whether the additional methamphetamine seized in recent years was manufactured clandestinely within the region. However the agency says this is impossible to determine.

According to UNODC’s 2015 World Drug Report, significant seizures of MDMA (ecstasy) have also been reported in Indonesia, with 489,311 tablets seized in 2014 alone – the largest amount out of any country in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia’s archipelago has vast, porous borders and millions of vehicles of all kinds transiting daily across its islands, which makes detection of trafficked drugs ever more difficult. A significant amount of drugs arriving from abroad are believed to enter the country concealed in cargo containers. Only around 2% of containers arriving in Indonesia are inspected.

Brown warned that the establishment of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Economic Community (AEC) at the end of last year, which aims to boost trade in the region, is a concern for law enforcers trying to contain supply.

“Drug networks, criminal networks, will take advantage of the freedom to cross borders – moving goods, moving people. Because that’s what they do, they piggyback on the increased movement of trade and goods to move their illicit materials,” he said.

“What affects Indonesia, affects the region, what affects the region, affects Indonesia. You need to facilitate trade but at the same time you need to put into place mechanisms that are going to respond to those potential threats,” he added.

Brown said UNODC has been working with Indonesian Customs and Excise Office through its container control program to facilitate intelligence sharing about ships and goods as well as to train custom officials on how to identify risk factors – “where is (the container) coming from, where is it transiting to, where is it going.”

But Brown believes law enforcement alone will not be sufficient to stop the transit of drugs and Indonesia should do more to tackle the demand for drugs.

“I don’t think it’s a matter of taking away the efforts of law enforcement or even reducing the efforts of law enforcement. I think it needs to be more balanced. You also have to cut your demand. And that is one of the criticisms that Mexico usually levels at the United States: look, you complain about the supply from down here, but you need to cut your demand up there.”

International isolation

Indonesia’s approach to drug eradication – not drug reduction – is shared by ASEAN, including the use of the death penalty. The regional grouping has set the complete eradication of drugs as one of its goals in its 2025 Vision even though the goal is widely seen as unachievable.

In persisting with this approach, Indonesia is increasingly distancing itself from the international consensus on the world drug problem.

A UN General Assembly special session on drugs in April, the first in almost two decades, approved an agreement to bring UN recommendations on drug policymaking in line with the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The document calls for demand reduction through evidence-based measures, voluntary participation of those with drug problems and the prioritization of medical treatment.

The document continues to include prohibitionist policies banning narcotics use, despite growing international discontent with the “war on drugs.” It also calls for sentences proportional to the severity of drug crimes – which does not include the death penalty.

The session saw an Indonesian delegate booed when he defended the country’s use of the death penalty as “an important component” of the country’s drug control policy. Nasution, who was present at the meeting, said “Indonesia is trying to isolate itself, not follow international consensus about how to deal with drugs issues.”

The government, he said, is playing two different roles. Some officials, particularly law enforcers, say all drug users should be eliminated while other officials say drug problems should be tacked with a more health-focused approach, as the UN advocates.

Nasution hopes President Widodo will reconsider Indonesia’s approach as more accurate data on Indonesia’s case becomes available. “I believe Jokowi does not understand the real situation, he just listens to the reports of his staff. Someone should speak directly to Jokowi about this reality and once he believes it, he will do what’s right.”

But even if drug policies are reformed to introduce fines or voluntary drug treatment instead of detention, the country will still need to deal with the after-effects of decades of anti-drug propaganda underpinned by more moral arguments than medical reasons.

Nasution says the ideological and moralistic paradigm that permeates drug policy discussions in Indonesia makes the topic sensitive. PKNI, for example, calls itself a network of drug victims, rather than a network of drug users.

For as long as drug use and demand reduction are seen as a matter for law enforcement, Indonesia is unlikely to deal effectively with the problem and will continue putting thousands of people at risk of social exclusion. Crime rates and concentrated epidemics of diseases like HIV could worsen due to mass incarceration of drug users, given the unsanitary conditions of jails and barriers to social reintegration after they leave prison.

A version of this article was first published by Concord Review on May 18, 2016. Free trial subscriptions are available.

Follow Concord Review on Twitter: Follow @i_concordreview